32 bits, 32 gigs, 1 click...

Exploitation of a JavaScriptCore WebAssembly Vulnerability

In this post we will examine a vulnerability in the WebAssembly subsystem of JavaScriptCore, the JavaScript engine used in WebKit and Apple Safari. The issue was patched in Safari 14.1.1. This vulnerability was discovered through source review and weaponized to achieve remote code execution in our Pwn2Own 2021 submission. A future post will detail the kernel mode sandbox escape.

WebAssembly Overview

WebAssembly, often dubbed wasm, is an assembly-like language with a binary representation primarily intended for use on the web. Compared to the highly dynamic and complex paradigm of JavaScript, WebAssembly is very simple (for now…). There are four primitive value types (32/64 bit integers and floats) coupled with a relatively small instruction set operating on a stack machine.

Like many assembly languages, wasm can be written by hand in a human-readable text format. Real world wasm applications, however, are typically built with a compiler. An increasing number of high-level languages are supporting compilation down to wasm, with projects like Emscripten opening up support to any language that uses LLVM.

The WebAssembly LLInt

When JavaScriptCore runs traditional JavaScript code, it utilizes four tiers of execution, which increasingly optimize code. When the engine decides a function is ‘hot,’ which may occur if it is called often, or contains a loop that iterates enough times, it is passed off to the next tier, undergoing more aggressive optimizations.

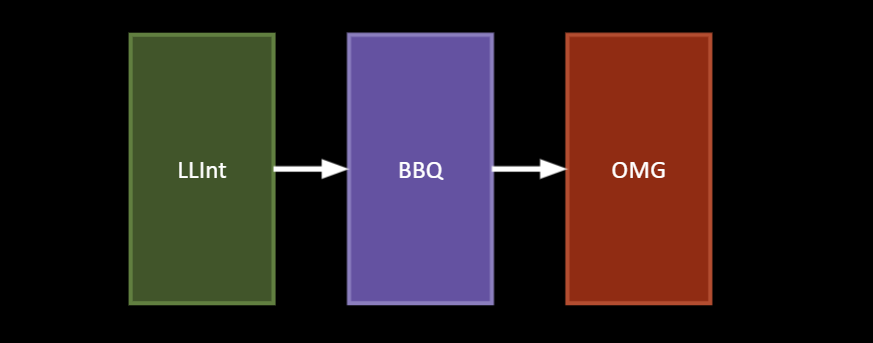

The wasm execution pipeline adopts a similar approach with three tiers. Parsing of WebAssembly modules generates bytecode to be consumed by an interpreter: the wasm llint (Low Level Interpreter). After the llint, there are two JIT (just-in-time) compilers: BBQ (Build Bytecode Quickly), and OMG (Optimized Machine-code Generator).

We will focus solely on the llint; in particular, the parsing and bytecode generation process. For each function within a wasm module’s code section, the function is parsed and bytecode is generated in a single pass. The parser logic is generic, and templated over a context object responsible for code generation. For the llint, this will be an LLIntGenerator object producing bytecode.

Parsing and Codegen

The parser will be responsible for verifying function validity, which will involve type checking all stack operations and control flow branches. Wasm functions have very structured control flow in the form of blocks (which can be a generic block, a loop, or an if conditional). Blocks are nested, and branching instructions can only target an enclosing block. From the parser’s point of view, each block will have its own expression stack, separate from that of the enclosing block. With the multi-value spec, each block can have a signature of argument types and return types. Arguments are popped off the current expression stack, and used as the initial values for the new block’s stack; return values are pushed onto the enclosing stack when branching out of the block.

The generic FunctionParser keeps track of the control stack and the types on the expression stack. The LLIntGenerator tracks various metadata, including the current overall stack size (cumulative over blocks) and the maximum stack size seen throughout parsing. The current stack size helps turn abstract stack locations into native stack offsets, and the maximum size will determine how much stack space to reserve during the function prologue.

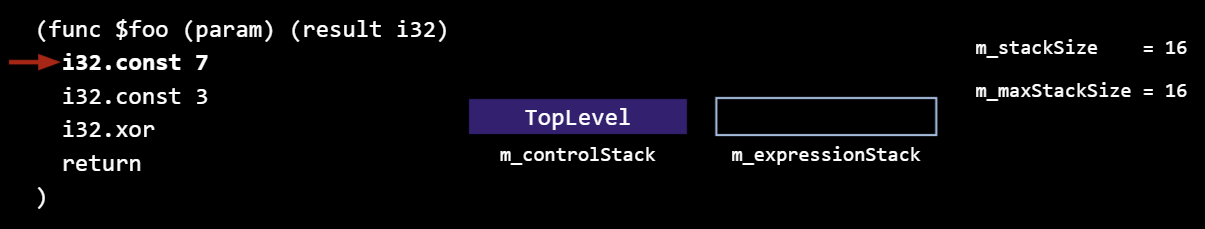

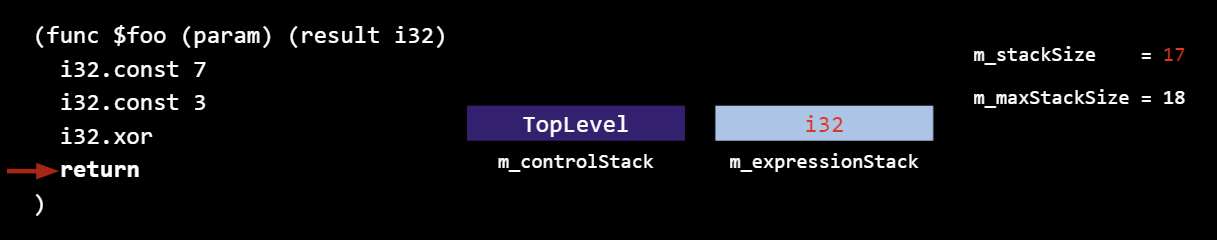

Let’s look at a few examples for some simple wasm functions. This function takes no arguments, and returns a 32-bit integer. Here is the parser/generator state before parsing any instructions:

As a note, the calling convention specifies that arguments are first passed in registers and then on the stack.The llint reserves stack slots for all possible argument registers regardless of whether the function accepts that many arguments or not. On x86_64, there are 2 callee-saved registers, 6 argument GPRs, and 8 argument FPRs, which is why m_stackSize starts at 16.

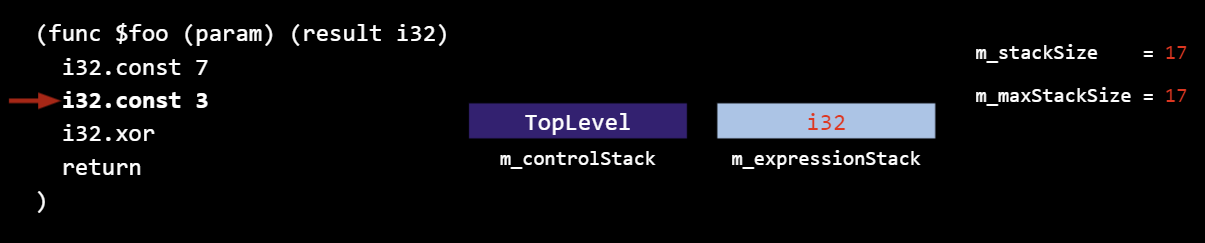

m_expressionStack tracks the types on the interpreter stack (not the values; this is just parsing, not execution). In this case, an i32 was pushed:

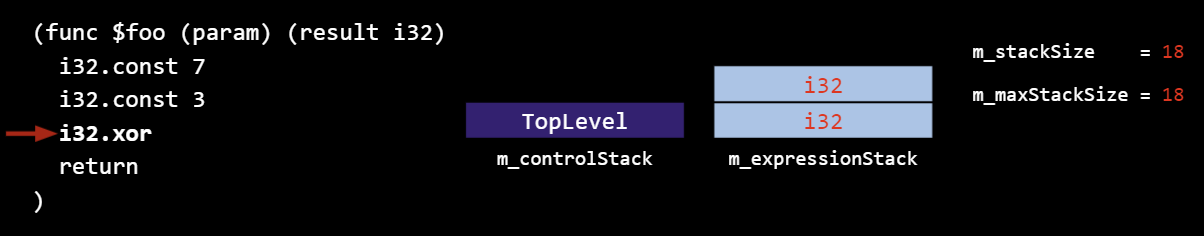

And another i32 push:

The xor will pop off the top two i32 operands and push an i32 result:

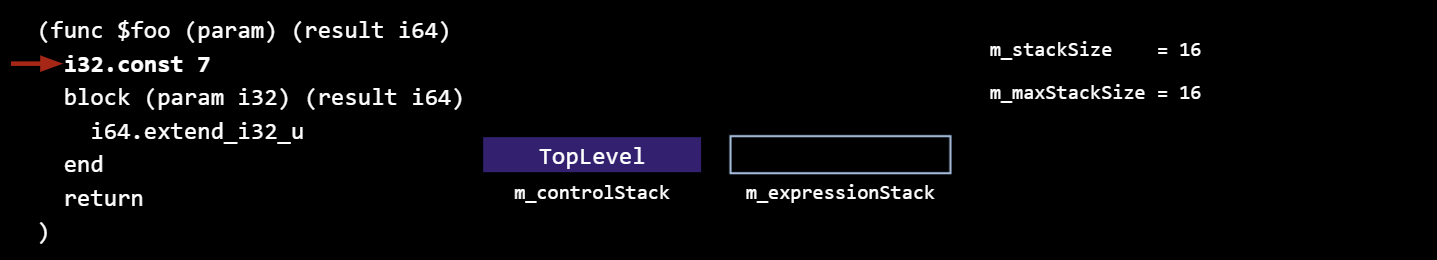

Now for an example with blocks. This function takes no arguments, and returns a 64-bit integer.

Initial state:

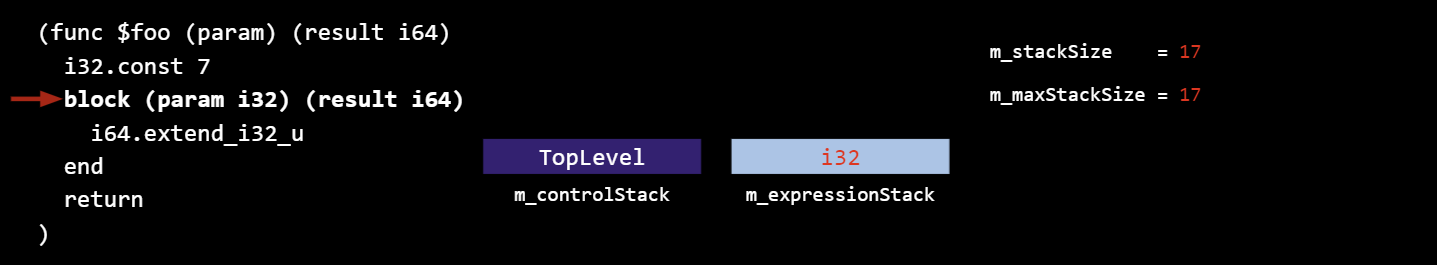

An i32 is pushed, incrementing the current stack size:

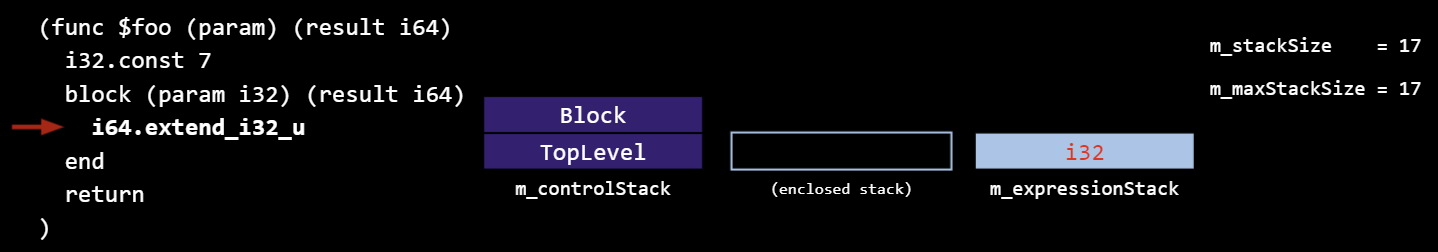

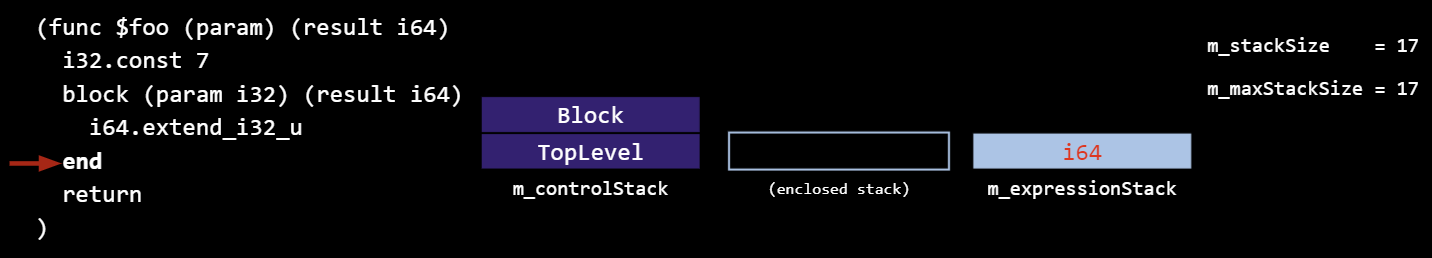

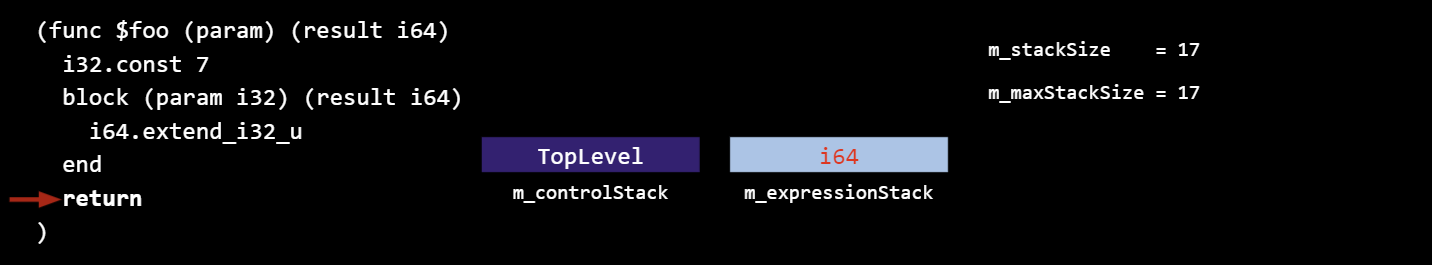

When we hit the block, a new expression stack gets created, and any arguments (in this case a single i32) are popped off the current stack and pushed onto the new. A control stack entry is created with a reference to the current stack (the enclosed stack), and the new stack becomes the current. The current stack size does not change.

The conversion instruction will pop the i32 off the stack and push an i64:

When ending the block, the block’s return types get moved onto the enclosed stack, the control entry is popped off, and the enclosed stack becomes the current (in a way, the control stack is a stack of stacks).

The Vulnerability

The m_maxStackSize field is intended to keep track of the maximum number of stack slots needed at any point within the function. It is updated in a few places, primarily on every push to the expression stack:

When parsing is complete, it is rounded up to account for stack alignment requirements (16-byte alignment, or 2 “registers” on x86_64), and stored in the m_numCalleeLocals field of the resulting FunctionCodeBlock

When the function is actually invoked, the llint prologue uses m_numCalleeLocals to determine the stack frame size (i.e. sub rsp, 0x...) and whether or not it is large enough to trigger a stack overflow exception:

By pushing enough times, m_maxStackSize can be set to UINT_MAX, or 0xffffffff. When parsing completes, LLIntGenerator::finalize rounds the max stack size up for alignment: rounding 0xffffffff up to a multiple of 2 induces an integer overflow, giving 0.

This leads to a 0 value for m_numCalleeLocals, which determines the stack frame size during the function prologue. Consequently, invoking the function will not allocate any stack frame space, and will not trigger a stack overflow exception. The function may in reality use as many stack slots as it pleases, while the llint believes no stack frame allocation is necessary…

Triggering the Bug in Practice

To trigger this bug, we will need to craft a wasm function that performs roughly 2^32 push operations. There may be other methods to achieve this, but the exploit ended up abusing the multi-value spec in tandem with the parser’s treatment of unreachable code.

The multi-value spec allows blocks to have any amount of return values, and JavaScriptCore does not enforce its own upper bound. This will allow us to craft blocks with a very large number of return values.

For unreachable code, the parser performs some very basic analysis to determine if code is unreachable, or dead code. For instance, an explicit unreachable opcode or an unconditional branch renders the code after it (within the same block) unreachable. When the block with unreachable code ends, the generator acts as if the block was well-formed, and pushes the declared return types onto the enclosed stack.

This may be required behavior in certain scenarios where one branch of an if-else throws an unreachable exception, and the other branch behaves normally. It would be wrong to reject the function as invalid on the grounds of the return value type-check failing, since the exception would break out of the function anyway.

In any case, we can abuse this behavior with the following pattern:

This allows us to push a considerable number of values onto the parser’s expression stack with very little actual code.

The natural thing would be to simply concatenate this pattern back to back to perform another N pushes, however a minor logistical concern prevents this. The expression stack is implemented with a WTF::Vector, which has a 32-bit size field, and performs proper checks on resize operations to ensure the allocation size does not exceed 32 bits. The elements of the vector are TypedExpression objects, which have a size of 8. This means the upper limit on the stack size is 2^32 / 8 = 2^29 = 0x20000000. The resize operations also don’t follow perfect powers of two, so the actual limit is somewhat less.

To deal with this, we can use nested blocks, since as seen in the previous walkthrough example, each nested block will have its own expression stack, i.e. its own vector.

By making each block have 0x10000000 return values, and nesting 16 such blocks, we can set m_maxStackSize to 0xffffffff, which will overflow once parsing is complete.

Each vector will use roughly 2GB, and with 16 of them that makes 32GB. This may seem impractical, but with the magic of macOS compressed memory, allocating and using all this memory takes roughly 2 and a half minutes (at least on a 2019 MacBook Pro with 16GB RAM, time will vary by hardware), which is well within the Pwn2Own time constraint of 5 minutes per exploit attempt.

Getting Leaks

With m_numCalleeLocals set to 0, when we execute the wasm function, the llint will not perform any subtraction for the stack frame, leading to the following stack layout:

| ... |

| loc1 |

| loc0 |

| callee-saved 1 |

| callee-saved 0 |

rsp, rbp -> | previous rbp |

| return address |

As briefly mentioned previously, loc0 through loc13 will be comprised of the 6 GPRs and 8 FPRs designated as potential arguments by the calling convention, so in order to access loc0 and loc1 we’ll want to accept 2 i64 arguments.

In the llint, certain operations are designated as slow paths, and are implemented by calling out to a native C++ implementation. Any native stack pushes that occur during the slow path handler have the potential to overwrite the callee-saved registers and locals pictured above. Our goal will be to choose one such slow path such that its invocation will overwrite loc0 and loc1 with a code address and a stack address. Then upon returning from the slow path, we can use the locals “normally” to perform arithmetic on the leaks as needed.

We will specifically call slow_path_wasm_out_of_line_jump_target. “Out-of-line” jump targets apply to branches with an offset too large to be directly encoded in the bytecode format. In our case, any offset of at least 0x80 will do, giving us something like this:

The above code pattern will perform a native call to slow_path_wasm_out_of_line_jump_target, which will have the illustrated effects when executed:

We now have a return address in loc0, which will point into the JavaScriptCore dylib, and a stack address in loc1, giving us the info leaks we need to achieve remote code execution.

There are likely other slow path handlers that would work just as well; this one was chosen for its simplicity, presumably increasing the likelihood that the exploit would work as-is on different WebKit builds.

Hopping the Fence

Remember that the function we can execute has no stack frame allocated for any of its stack-based operations. For instance, a push operation may write to the native stack at say, rbp-0x40, then the following push operation would write at rbp-0x48, and so on without restraint. So in theory, the function should be able to write to out-of-bounds stack slots (with large negative offsets, e.g. rbp-0x10000). This would allow us to overwrite whatever memory is below the current stack.

This isn’t very helpful in the context of the main thread, as there is nothing mapped below the main thread’s stack (at least, not at a reliable and known offset). Threads, however, have their stacks allocated contiguously at increasing addresses from a dedicated virtual memory region. For example:

STACK GUARD 70000b255000-70000b256000 [ 4K ] ---/rwx stack guard for thread 1

Stack 70000b256000-70000b2d8000 [ 520K ] rw-/rwx thread 1

STACK GUARD 70000b2d8000-70000b2d9000 [ 4K ] ---/rwx stack guard for thread 2

Stack 70000b2d9000-70000b35b000 [ 520K ] rw-/rwx thread 2

If we imagine the buggy wasm function executing in thread 2, the stack for thread 1 would be the corruption target. The only problem is the guard page… Luckily for us, the llint has a few more tricks up its sleeve in the form of primitive optimizations.

When pushing a constant value, the generator does not actually emit an instruction to write the constant value to the stack slot. Instead, it adds the constant to a “constant pool” and any subsequent reads from that stack slot will fetch from the constant pool instead of the stack. Any writes to the stack slot will, indeed, perform a write. The constant can also be “materialized” (which explicitly writes the constant value to the stack) in certain control flow scenarios, but it is fairly easy to avoid such a scenario by not having control flow.

To illustrate what this means, consider the following snippet:

During execution of this snippet, the only value written to the native stack would be 5, for the addition 3+2.

This behavior will enable us to easily hop over the guard page by pushing a large number of unused constants.

ROP

In a manner very atypical of modern browser exploitation, by overwriting values on the victim thread’s stack, we can immediately obtain ROP. There will be no incremental progression of building up stronger and stronger primitives, no addrof or fakeobj necessary; just a good old fashioned ropchain.

Our leaked pointers are stored in locals, so writing a gadget might look like this:

And similarly for writing any stack addresses we need, using local.get 1 as the base instead. Writing constants can be done by performing a bitwise or with 0.

In order to obtain shellcode execution, our ropchain will need to do some non-trivial work. With SIP enabled, rwx protections for a page are only allowed if a particular flag, MAP_JIT (0x800), was specified during the page’s creation with mmap. Since the thread stack wasn’t mapped with this flag specified, we can’t simply mprotect our shellcode on the stack and return to it.

Instead, we will use a function ExecutableAllocator::allocate as intended to reserve an address in the existing rwx JIT region, memcpy our shellcode there, and then return to it. This first stage shellcode can be a short stub to download a larger second stage shellcode, e.g. the sandbox escape exploit.

To recap and put all the pieces together, our wasm function will have roughly the following form:

Conclusion

The integer overflow vulnerability was patched in Safari 14.1.1, with an assigned CVE ID of CVE-2021-30734. The patch utilizes checked arithmetic within the generator for the various stack size operations.

The exploit source code is being released for educational purposes, and can be found here.

Having achieved arbitrary code execution within the browser’s renderer process, the next step in the typical exploit chain is some form of sandbox escape, usually targeting a more privileged process or the kernel. In an upcoming post, we will walk through how we exploited a kernel driver to obtain arbitrary kernel code execution.